By Rodolfo Roman-Guzman (January 10, 2026)

I recently read The Invention of Morel by Adolfo Bioy Casares for the second time. The first time was more than thirteen years ago, when I was still a medical student and an avid reader of Latin American authors, having accepted—though not without a certain resignation—that the dream of becoming a writer could only be lived on weekends. At that time, my identity seemed to be torn between two characters: one was a medical student, rigorous with himself, absorbed by coursework, exams, and the discipline of weekdays. The other, quieter and deeply nostalgic, withdrew on weekends to lose himself among books and poetry in the corridors of the library, as if literature were a kind of refuge from an overwhelming and demanding reality.

Returning to this novel so many years later, no longer as a student but as a neurologist, was a different experience. And who has not gone through something similar when rereading a short story or a novel? The text remains intact, but the reader is no longer the same. That is exactly what happened to me: where I once saw only a fantastic story about immortality and impossible love, other, deeper axes began to emerge with clarity—questions that had gone unnoticed at the time and that I will try to explore next.

But let us return to the point of departure. In The Invention of Morel, Bioy Casares imagines an island where Morel has created a machine capable of recording a group of people in their entirety: image, voice, gestures, and, unsettlingly, something that resembles their consciousness. These recordings are reproduced eternally, frozen within a perfect loop. The price of this feat, however, is radical: the biological death of the original individual. Morel thus pursues an extreme form of immortality—fixing forever an ideal moment of his life alongside Faustine, the woman he loves. Yet what the machine preserves is not life itself, but merely its appearance: a memory without a timeline, a presence deprived of any possibility of change. The images of that week on the island repeat themselves endlessly.

The narrator and protagonist of this story is a fugitive who arrives on the island where Morel carried out his masterpiece. Shortly after settling in, he realizes that he is not alone. In an almost hypnotic manner, he describes how he watches Faustine approach each afternoon the hill that overlooks the beach. The landscape is luminous and serene: the sea stretches below, motionless, while the sun slowly descends, bathing everything in a golden light. Faustine walks with a calm, measured pace, completely unaware of the one who observes her, and always stops at the same spot, from which she fixes her gaze on the horizon. The fugitive, hidden from view, follows her with obsessive attention; he knows exactly where she will stop, how she will turn her body, how long she will remain still, as if he were witnessing a scene rehearsed down to the smallest detail.

Faustine’s beauty overwhelms him. Yet, despite following her relentlessly, she never reacts to his presence. She does not see him, does not hear him, does not startle— not even when he deliberately places himself in front of her or speaks directly to her. As the days pass, the fugitive begins to notice something even more disturbing: conversations, walks, gestures, and scenes repeat themselves in an identical manner, as if time had become trapped in an eternal spiral. He even comes to anticipate with precision every movement of Faustine and of the other visitors.

Eventually, the fugitive becomes gravely ill. Living in hiding among the island’s swamps, exposed to constant humidity, poor nourishment, and a probable tropical infection, leaves marks that are profoundly human and real. He develops fever, his physical condition progressively deteriorates, and an intimate conviction begins to take hold in him: that he is going to die.

His state of physical decay strikes me as one of Bioy Casares’s greatest achievements, for it stands in brutal contrast to the absolute immutability of Faustine and the other vacationers, who neither fall ill nor age. This difference reinforces the certainty that they are not alive, but rather belong to another existential plane. And when the fugitive finally understands how Morel’s machine works—a device that records people at the cost of their lives—his illness acquires a definitive meaning. Once he becomes aware that there is no longer any real alternative for survival, he decides to surrender voluntarily to the invention and accept his biological death, in the hope of eternalizing himself, even if only as an image, alongside Faustine.

In the novel, it seems significant to me that Bioy Casares never allows these two characters to coexist within the narrative timeline: Morel has already acted by the time the fugitive arrives on the island. However, I believe that the apparent split between the fugitive and Morel can be read not as two parallel stories, but as two instances of a single, divided consciousness. Morel would represent the omnipotent self—creative, narcissistic, capable of sacrificing Faustine and the others in the name of a perfect eternity—whereas the fugitive embodies a being condemned to lack, bodily deterioration, illness, and unanswered waiting.

Around the same days in which I was rereading The Invention of Morel, I happened to care for a very peculiar case of a patient with Alzheimer’s disease dementia. During the consultation, his wife told me that months earlier they had been visited by one of their nieces—his favorite niece, specifically—who had stayed with them during the spring for no more than a week. They were never able to have children, and for him, his niece represents the closest bond to having a daughter. Perhaps this explains why the patient seemed to be so deeply affected by that visit.

The man is in a state of severe amnesia, yet since that spring he has remained fixated on the idea that his niece is still in the house. Almost daily, long after her departure, he looks for her in the guest bedroom to tell her that breakfast is ready; he interrupts his routine to include her as part of it. His wife explained to me that the week he spent with his niece remained, in some way, fixed within him. The man constantly confabulates about his niece’s visit. He has no idea what date he is living in, yet he searches for her every day, as if he had become stuck in that week when his niece came to visit.

And as I interviewed this patient and his wife, I could not help but draw a parallel between his case and what I was reading. In a certain sense, this man and the fugitive experience a similar phenomenon, one in which the mind plays with reality and memory. That very afternoon, I became immersed in a search to better understand the neurobiological mechanisms underlying confabulation.

Korsakoff was among the first to observe that alcoholic patients with amnesia exhibited pseudoreminiscences, in which they produced detailed events that had never occurred, sometimes blending them with real events from the present. Early attempts to understand confabulation from a neurobiological perspective began to show that it was not simply a “failure of memory,” but rather a deeper alteration in the relationship between thought and reality. In his classic work on spontaneous confabulation and the adaptation of thought to ongoing reality, Schnider proposed that this phenomenon emerges when the brain loses the ability to filter which mental representations are relevant to the present moment. In other words, the problem is not merely remembering incorrectly, but not knowing which memory belongs to the now.

From this perspective, spontaneous confabulation has been consistently associated with lesions in the medial orbitofrontal region, a critical area for evaluating the contextual relevance of evoked information. This region does not “store” memories, but it fulfills an essential function: it suppresses representations that, although plausible, no longer correspond to current reality. When this mechanism fails, thoughts or memories that are irrelevant—yet emotionally charged—can impose themselves as true.

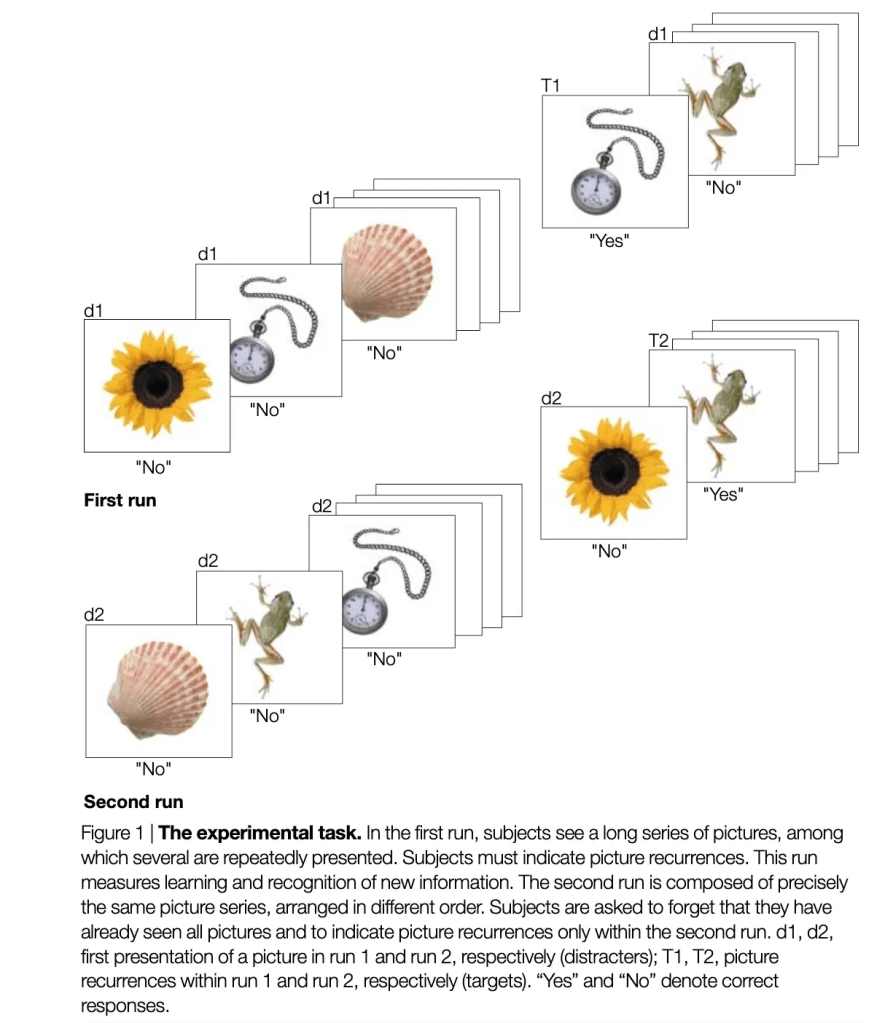

To explore this phenomenon, Schnider and his group designed an experiment that was apparently simple (see image below), yet conceptually very sophisticated. Its aim was not to measure memory per se, but rather the capacity of thought to adapt to the reality unfolding in the present moment. In the first phase, participants were presented with a long sequence of images. Some of these images reappeared within that same sequence, and the subject’s task was simply to indicate when an image was repeated. In this initial run, any stimulus that felt familiar could legitimately be assumed to be a repetition, so this phase evaluated, in a fairly direct manner, the ability to learn and recognize new information.

But the crucial point of the experiment did not lie there, but rather in what happened afterward. Approximately one hour later, participants were again exposed to the same complete set of images, now arranged in a different order. Before beginning, they were given a key instruction: they were to forget that they had already seen all of the images before and indicate only those that were repeated within this second presentation. In other words, they were to respond “yes” only if an image reappeared during the course of this second run, and not simply because it felt familiar.

Image credit: Schnider A. Spontaneous confabulation and the adaptation of thought to ongoing reality. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 5):1085–1096. doi:10.1093/brain/awg104

In this second phase, the task could no longer be solved by appealing to familiarity. All of the images were, by definition, familiar. Performance now depended on something far more subtle: the ability to distinguish whether the sense of recognition evoked by an image corresponded to immediate reality—that is, to a repetition within the present run of the task—or whether, instead, it arose from a past that was no longer relevant, namely the experience of the first run. The subject had to decide whether that memory belonged to the “now” or to a “before” that had to be actively ignored.

It was precisely in this second phase that patients with spontaneous confabulation displayed a distinctive pattern. Unlike healthy subjects and amnesic patients without confabulation, their performance deteriorated markedly. They not only made more errors, but also, in a systematic way, tended to affirm that images new to the second run had already been repeated, producing a significantly higher number of false positives. Moreover, they did so with full conviction, as if familiarity alone were sufficient to impose certainty.

These findings suggest that, in spontaneous confabulation, the problem does not lie solely in learning or remembering, but in something more profound: the inability to suppress activated memories that are irrelevant to ongoing reality. The mind recognizes, but fails to discriminate; it remembers, but cannot correct itself against the present. Thought, then, ceases to adapt to the now and becomes trapped in a narrative that, although coherent, no longer corresponds to the world that is unfolding. This is precisely what happened to my patient with Alzheimer’s disease, who confabulated about his niece’s presence in the house, incorporating that image into his daily routine despite the fact that her visit had taken place long before. Thus, confabulation can be understood as a disorder of the adaptation of thought to ongoing reality. The brain continues to generate coherent narratives, but it has lost the ability to subject them to contextual plausibility checks. The result is not chaos, but something perhaps more unsettling: a false reality that is internally consistent.

In this sense, the situation faced by the patient with Alzheimer’s disease who searches daily for his niece is not very different from that of the fugitive in The Invention of Morel. In both cases, the mind clings to a meaningful representation of the past and projects it onto the present without the possibility of correction. The difference is that, while in the novel repetition is produced by an external machine, in confabulation it is the brain itself that has lost the capacity to shut down scenes that no longer belong to the now.

However, as I continued to investigate, I found that this mechanism can adopt even more radical forms. A particularly illustrative example of the mind’s rebellion is the case reported by Zhang and colleagues, in which confabulation is no longer confined to an affective fragment of the past, but instead invades the entire experience of the present. The case involves a man in his eighth decade of life, previously independent, who developed insidiously a persistent conviction that everything new had already happened before. This was not a fleeting sense of familiarity, but an unshakable certainty: the news, television programs, his e-book reader, people on the street, and the places he visited repeated themselves exactly day after day.

The patient constructed detailed and firm explanations to justify this experience, without accepting external correction. He did not present hallucinations or structured delusions in the classical psychiatric sense, and his autobiographical memory remained relatively preserved. What was altered was not so much the content of his memories, but the capacity to recognize novelty as such, since for him everything had already occurred before. The present became indistinguishable from the immediate past.

This phenomenon, described as déjà vécu accompanied by confabulation, became omnipresent and progressively more distressing. Neuropsychological evaluation revealed rapid forgetting and executive dysfunction, followed by a gradual cognitive decline. Brain MRI showed generalized cerebral atrophy with left temporal predominance; FDG-PET demonstrated left temporal and bifrontal hypometabolism; and cerebrospinal fluid analysis was consistent with probable Alzheimer’s disease. Despite various therapeutic attempts, the symptoms persisted and slowly progressed over the course of follow-up.

This case is particularly revealing because it exposes, in an almost experimental manner, what happens when the brain completely loses the ability to filter which experiences belong to ongoing reality. It is no longer a matter of confabulating around an isolated scene, such as a niece’s visit, nor of becoming trapped in a perfect week, as on Morel’s island. Here, the entirety of the world turns into repetition. Time ceases to move forward because the present has lost its status as novelty.

From this perspective, The Invention of Morel ceases to be merely a novel about immortality and becomes an unsettlingly precise allegory of human memory. Morel’s machine does not create copies of the past; it annuls the present. In the same way, in confabulation associated with Alzheimer’s disease, the brain does not “remember too much,” but rather fails to suppress what no longer belongs to the now. The result is an artificial eternity—coherent and profoundly false—in which the mind becomes trapped without any possibility of correction.

This series of readings and clinical encounters inevitably led me to reflect on the role of memory and time in the construction of the individual. Gabriel García Márquez once wrote that life is not what one lived, but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to tell it. An uncomfortable but necessary question then arises: do memories belong to the individual or to time? Do they possess an identity of their own, or do they exist only in relation to the one who evokes them?

At first, the fugitive discovers in Faustine’s holograms a form of companionship, a minimal hope with which to inhabit the island’s solitude. And when he comes to understand the true nature of her presence, far from renouncing his love for her, he chooses to surrender his life to a shared eternity—an artificial allegory, yes, but an eternal one. Perhaps this choice is not guided by reason, but rather by a deeper and more fervent sentiment.

The patient who searches daily for his niece and organizes his routine around her anachronistic presence shares something essential with this story. His love for her transcends amnesia. In his mind, time has ceased to function as a reliable organizing axis; when memories lose their temporal coherence, affect asserts itself as the criterion of reality. Memory, even when fragmented, continues to give shape to the world.

Perhaps this is why The Invention of Morel continues to speak to us with such force. Because it reminds us that memory does not merely preserve the past—it constructs the present. And when that mechanism fails—whether through a machine or through disease—what is lost is not only the sense of time, but something more profound: the ability to distinguish between what was, what is, and what we wish to remain forever.

Literary References

- Bioy Casares A. The Invention of Morel. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Emecé Editores; 1940.

- García Márquez G. Living to Tell the Tale. Bogotá, Colombia: Editorial Norma; 2002.

Medical and Neuroscientific References

- Schnider A. Spontaneous confabulation and the adaptation of thought to ongoing reality. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 5):1085–1096. doi:10.1093/brain/awg104

- Zhang X, Breen N, Parratt K. Déjà vécu with recollective confabulation: an unusual presentation of Alzheimer’s disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2023;16:e255411. doi:10.1136/bcr-2023-255411

- Moulin CJA. Disordered recognition memory: recollective confabulation. Cortex. 2013;49(6):1541–1552. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2012.10.003

- Korsakoff SS. Étude médico-psychologique sur une forme des maladies de la mémoire. Rev Philos. 1889;28:501–530.

Leave a comment