By: Rodolfo Roman-Guzman (December 7, 2025)

A few days ago, while watching some documentaries on YouTube—one of my favorite pastimes—I came across the story of Daniel Kish and the extraordinary work he has done to spread a technique that has transformed the lives of many blind individuals. Echolocation is not only a different way of perceiving the world; it is also the visible expression of a profound capacity for cerebral remodelling. Kish was born with bilateral retinoblastoma. His right eye was removed at seven months of age, and the left at thirteen; deprived of both eyes in order to save his life, he explains that he developed, almost naturally, another way of relating to his surroundings. As a baby, he began to explore without even understanding that he could not see; he describes how, just a few days after surgery, he lay restlessly in his crib, driven by that innate urge to discover.

With time, as naturally as seeing, hearing, touching, or tasting, a singular sense emerged in him: he began to use his tongue, his vocal cords, and other phonatory mechanisms not only to speak, but to produce clicks—tiny acoustic detonations that travelled through space, struck objects, and returned as echoes. Depending on the size, distance, depth, or movement of whatever they encountered, these echoes acquired different qualities, and upon reaching Kish’s ears, they revealed to him the invisible architecture of the world. And perhaps “invisible” is an unfair term in Kish’s case, for while the world assumed he could not see, his brain reorganized itself in such a way that he ended up “seeing” in a manner analogous to bats. Today, Kish has become a figure of hope for the blind community—so much so that one might say, without too much exaggeration, that he is a kind of real-life superhero, a real-life “Daredevil.”

But beyond Kish’s fascinating story, his way of seeing the world reminded me of a pair of readings that shaped my personal worldview years ago. I first thought back to Blindness, by José Saramago. In this novel, an entire city is struck by sudden blindness. If my memory isn’t playing tricks on me, it begins with a man driving his car who is abruptly engulfed by an aureal glow—the so-called white blindness—and ends up in an accident. From that moment on, Saramago unfolds a human odyssey that follows several characters as they struggle to survive the collapse of their visual world. Along that journey, the worst and the best of humanity emerge: betrayals, violence, unexpected alliances, and ethical fissures that reveal a fragility that perhaps had always been there.

Among that group of protagonists, “the old man with the black eyepatch” stands out, joining them when they are all confined in an asylum. That image of the asylum— a space designed to contain madness—functions as a metaphor for the absolute disorientation that engulfs people who have suddenly lost the sense that shapes much of human experience: sight. The old man with the black eyepatch is the only true blind person, someone who was already living without vision before the epidemic. His presence offers practical knowledge, yes, but above all it reveals that the central theme of the novel was never physical blindness; rather, it is moral, social, and political blindness that structures the tragedy.

And it is difficult not to carry that reflection into our own reality. Who among us has not, at some point, encountered a blind person trying to orient themselves in a world built almost exclusively for those of us who can see? More than that, we have designed systems meant to “include” them without the designers truly understanding what they need. It often seems as though political ideologies—on either end of the spectrum—are so intent on “defining new minorities” or “fighting against them” that we have become blind to what is genuinely essential.

In 2020, an estimated 43.3 million people were living with complete blindness worldwide (Bourne, Rupert et al., The Lancet Global Health, 2021). But if we broaden our view to include low vision or moderate-to-severe visual impairment—that is, significant loss of near or distance vision—the number skyrockets: more than one billion people experience some degree of visual impairment, according to the World Health Organization. Thus, the experience of living without sight is far from marginal.

Kish himself insists on the need to transform the educational paradigm for blind individuals. He proposes creating training centers where blind youths receive guidance from other blind people who have already learned to navigate the world without sight, using strategies such as echolocation. And this makes perfect sense: who better to accompany a child who has lost their vision—or who never had it—than someone who has walked that same path and discovered other ways of perceiving?

At Kish’s foundation, World Access for the Blind, the images speak for themselves and defy any prejudice: groups of blind individuals hiking, riding mountain bike trails, or teenagers on skateboards, moving with a confidence that surprises even those of us who can see. It is a profoundly inspiring sight from a social standpoint and, at the same time, it sparks a legitimate scientific curiosity: how do they do it? With every example, Kish seems to remind us that the “impossible” is nothing more than an abstract idea—one that dissolves when human ingenuity, cerebral plasticity, and sheer will converge.

In contrast to the world of the blind in José Saramago’s Blindness, H. G. Wells had written another extraordinary tale years earlier: The Country of the Blind. Wells is better known for The Time Machine or The War of the Worlds. For many, he is considered “the father of science fiction,” and indeed the scientific rigor and instinct that shape his work are undeniable.

In The Country of the Blind, Wells describes the way of life of a mystical land situated “five hundred miles or more from Chimborazo, a hundred and fifty from the snows of Cotopaxi, in the wildest reaches of the Ecuadorian Andes.” To this place had come, many years before, “a handful of people, one or two families of Peruvian mestizos fleeing the lust and tyranny of a certain Spanish governor,” who, after “the formidable eruption of Mindobamba, when darkness fell over Quito for seventeen days and the waters boiled at Yaguachi and fish floated dead as far away as Guayaquil; when landslides swept the whole Pacific slope, the snows melted in sudden torrents, and floods tore through the valleys, and an entire face of the old Arauca crest broke away and fell with a mighty crash, cutting the Country of the Blind off forever from the exploring footsteps of humankind.”

Thus, this isolated land became home to a community afflicted by a strange disease that had left all those born there blind. “The disease ran its course through the small population of that now isolated and forgotten valley. The old became half-blind and groped their way about, the young saw only dimly, and their children saw nothing at all.” But sighted people had lost their vision so slowly that they scarcely noticed the change in their lives, and their lineage survived “Generations came and went. They forgot many things and invented many others. The tradition of the great world from which they had come took on a mythical and uncertain character. In everything except sight they were strong and capable, and soon genetic and hereditary chances produced among them one with an original mind capable of speaking and persuading others, and then another. Both died leaving their mark, and the small community grew in number and in knowledge, facing and solving the social and economic problems that arose.”

Some time later, a mountaineer named Nuñez, who worked as a guide for an English expedition, accidentally falls down the cliffs that isolate the mysterious region of the blind. He survives the fall and is astonished by the inhabitants’ way of life. The settlement—designed by blind people to be inhabited by blind people—is simple yet organic. “The houses in the center of the village did not resemble the improvised and irregular clusters of mountain towns he knew; they rose in a continuous row on either side of the main street with astonishing neatness; here and there a doorway broke through their multicolored façades, and not a single window interrupted their uniform front.” In his interactions with the inhabitants, Nuñez arrives believing that his ability to see will make him their ruler, recalling the proverb “in the country of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.” However, the villagers interpret his vision as a form of mental illness, rejecting his attempts to impose himself or explain the outside world. After failing to rebel, he ends up living as one of them; he falls in love with a young woman named Medina-Saroté and wishes to marry her, but the elders demand that his eyes be removed to “cure him”—an idea that terrifies him and forces him into a profound dilemma: preserve his love or his eyes. Ultimately, he chooses the latter and manages to escape the Country of the Blind.

What was happening biologically in that remarkable lineage of The Country of the Blind? This is where I find a beautiful parallel with the adaptive phenomena of the human brain when visual stimuli are interrupted early in life and compensatory mechanisms—such as echolocation—emerge. In Wells’s descriptions, those generations born and raised without sight developed new ways of understanding their surroundings; something very similar occurs, in biological reality, within the human brain deprived of vision. Neuroscientific evidence shows that when visual input disappears during the first years of life, the occipital cortex—traditionally considered “visual”—does not remain inactive: it reorganizes, reallocates its functions, and begins to process auditory, spatial, and tactile information with remarkable efficiency.

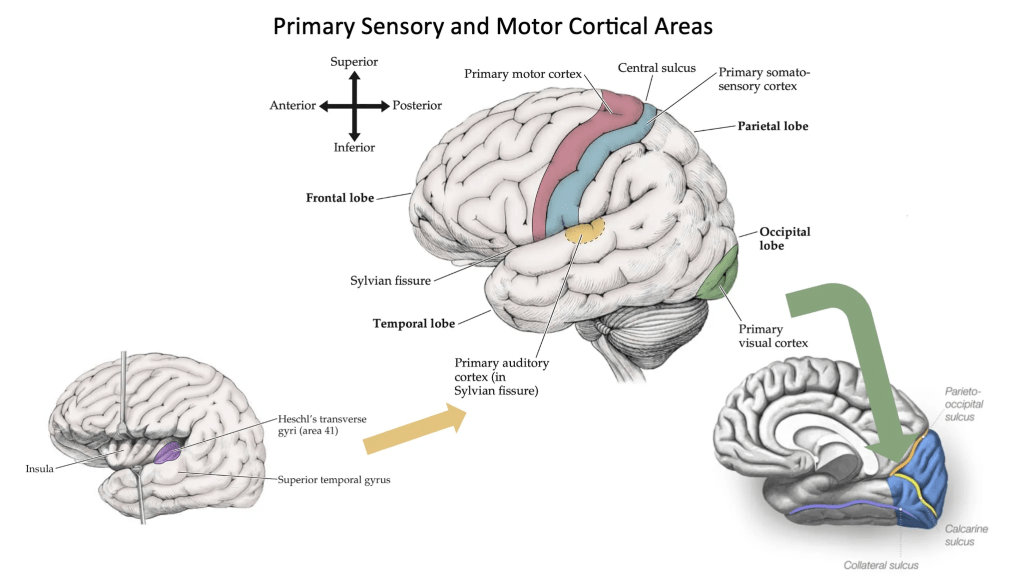

But before we dive fully into the studies on cortical remodelling in echolocation, I would like to briefly summarize the basic principles of how the cerebral cortex functions under normal conditions. It is worth recalling that the cortex contains what we call primary areas. The primary motor cortex (area 4) is located in the precentral gyrus of the frontal lobe. This area controls movement on the opposite side of the body. The primary somatosensory cortex (areas 1, 2, and 3) lies in the postcentral gyrus of the parietal lobe and participates in sensation from the opposite side of the body. Notice that the precentral and postcentral gyri are separated by the central sulcus, and that motor areas lie anterior to somatosensory areas. The primary visual cortex (area 17) is situated in the occipital lobes along the banks of a deep sulcus called the calcarine fissure. The primary auditory cortex (area 41) is composed of the transverse gyri of Heschl, two finger-like gyri located within the Sylvian fissure on the superior surface of each temporal lobe.

Image credit: Slide created using images from Neuroanatomy through Clinical Cases, Third Edition, Hal Blumenfeld, M.D., Ph.D., Yale University School of Medicine.

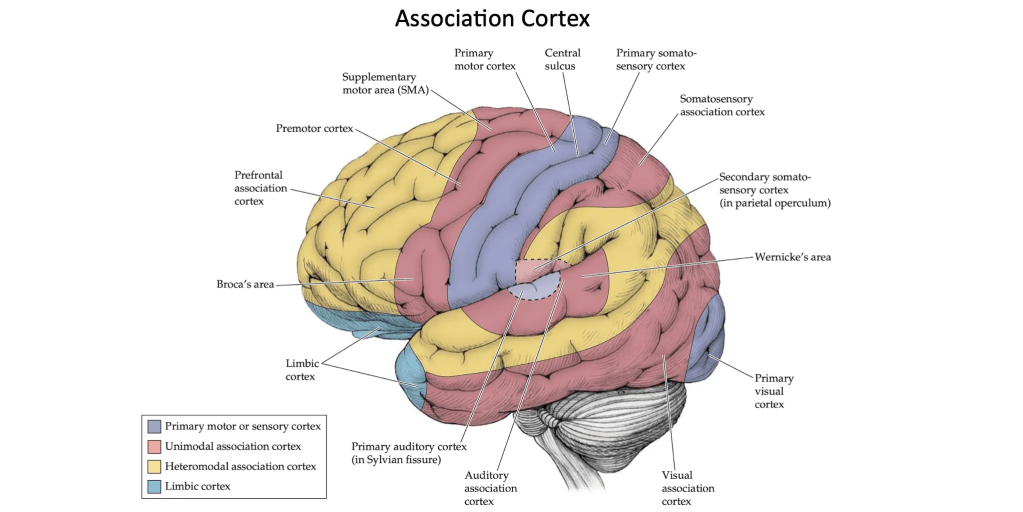

Moreover, the cerebral cortex contains a large number of association areas responsible for processing complex or higher-order information. Within these association cortices, two main types can be distinguished. On the one hand, there are unimodal association areas, which process information arising from a single sensory or motor modality and are located adjacent to their corresponding primary areas. For example, the unimodal visual association cortex lies just anterior to the primary visual cortex. On the other hand, heteromodal association areas integrate information from multiple sensory and/or motor modalities, allowing for a broader and more complex representation of the environment and of the actions that can be taken within it.

Image credit: Slide created using images from Neuroanatomy through Clinical Cases, Third Edition, Hal Blumenfeld, M.D., Ph.D., Yale University School of Medicine.

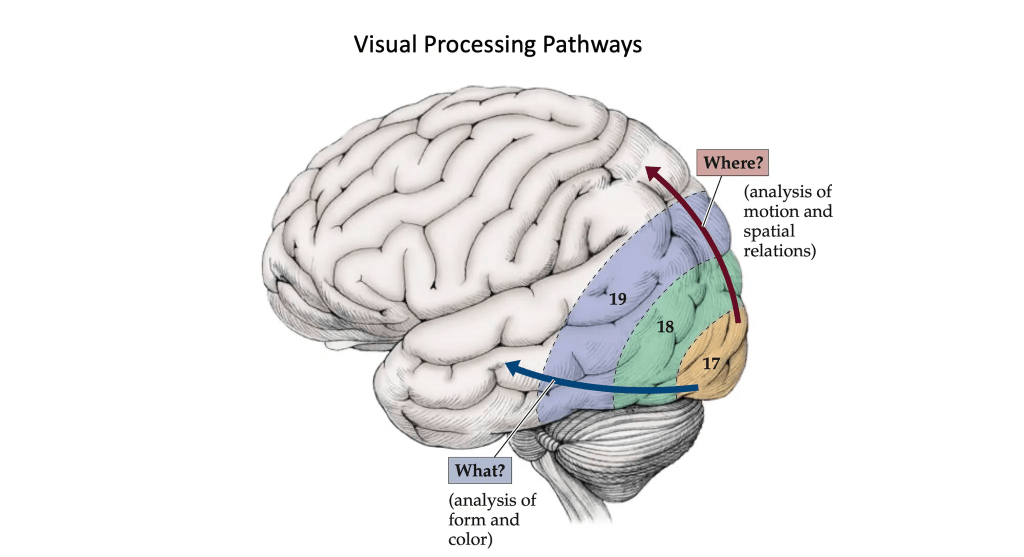

But these association areas become even more fascinating when we consider that they form circuits that give meaning to sensory stimuli. Specifically, for visual information, neurons in the primary visual cortex (area 17) project to association areas, including areas 18 and 19, which interpret movement and spatial relationships. From areas 17 and 18, two major pathways of higher-order visual processing emerge:

- The dorsal stream projects to the parieto-occipital association cortex. This pathway answers the question “where?” by analyzing movement and the spatial relations among objects, as well as the relationship between our own body and visual stimuli.

- The ventral stream, by contrast, projects to the occipitotemporal association areas. This pathway answers the question “what?” by analyzing form, with specific regions capable of identifying colors, faces, letters, and other visual stimuli.

Image credit: Slide created using images from Neuroanatomy through Clinical Cases, Third Edition, Hal Blumenfeld, M.D., Ph.D., Yale University School of Medicine.

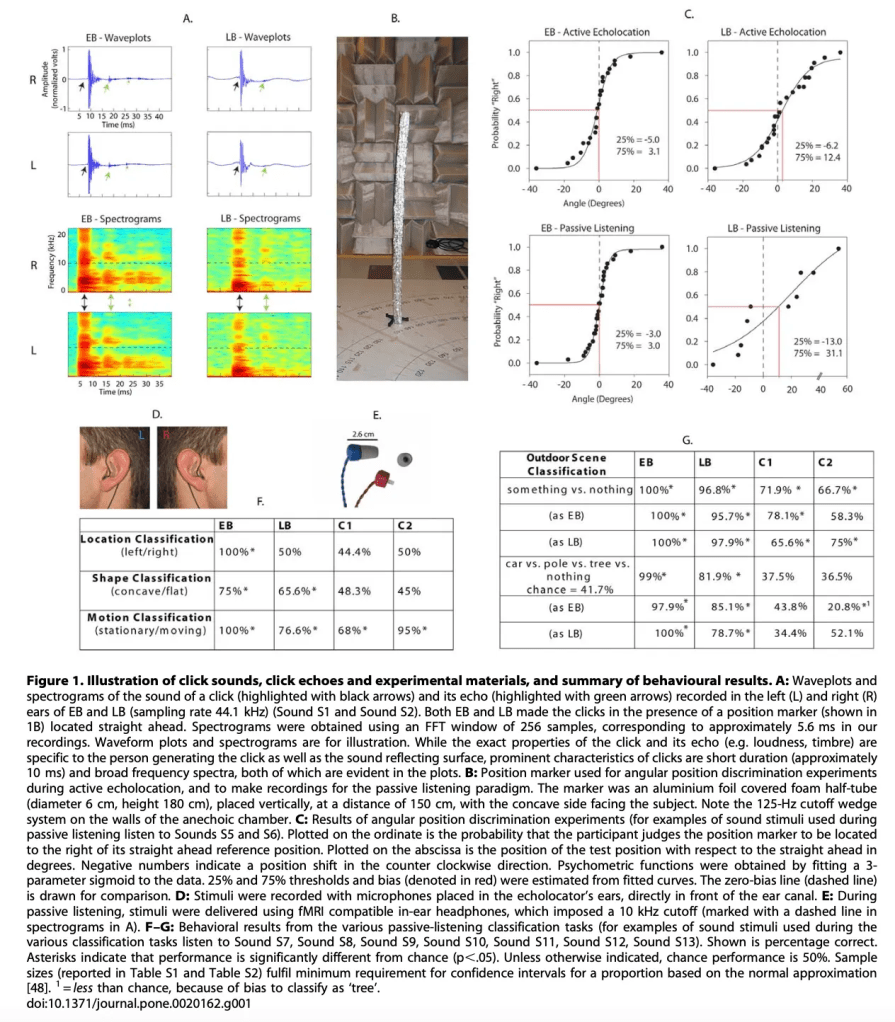

Now, how is it that, in the absence of vision, these cortical pathways reorganize themselves to process acoustic information in expert echolocators? Lore Thaler and colleagues explored this question in a fascinating functional MRI study involving four participants: two expert echolocators and two sighted controls. The first expert, identified as EB (“early blindness”), was 43 years old and had lost both eyes at 13 months due to bilateral retinoblastoma; as a result, he developed a natural form of sound-based orientation from a very early age. The second, LB (“late blindness”), was 27 and had lost his sight at 14 because of optic nerve atrophy; although his visual deprivation occurred later, he had also managed to turn echolocation into an everyday tool—using it to navigate, hike, ride mountain bike trails, and even play basketball. The two control participants, C1 and C2, were matched in age to EB and LB, respectively.

But this was not a simple experiment. Before placing participants in the scanner, the researchers had to carefully record each individual’s clicks and the echoes those clicks produced, since it is impossible to perform MRI scans while participants go around “clicking” through a city. Using these recordings, they later assessed each participant’s responses to both active and passive echolocation stimuli. They evaluated their ability to classify the location, shape, and motion of different objects, measuring accuracy. They also examined performance in a more complex outdoor scene, asking participants to discriminate “something versus nothing,” and further distinguish among a car, a pole, a tree, or the absence of any object.

Figure 1 summarizes this first phase of the experiment, and it is here that differences between participants begin to emerge. EB, for instance, showed an extraordinary performance: in the classification of outdoor scenes—distinguishing “something” versus “nothing”—he reached nearly 100% accuracy, and his ability to differentiate among specific objects such as a car, a pole, or a tree also remained close to 100%, far above chance level. LB, although he had lost his vision much later in life, demonstrated a remarkable performance as well: he exceeded 95% accuracy in distinguishing something versus nothing, and although his precision decreased slightly when required to discriminate among specific objects, he still showed a performance clearly superior to that of the controls. In contrast, C1 and C2—with normal vision and no echolocation training—collapsed in these more complex tasks: their accuracy in differentiating specific objects fell below 40%, barely above chance, underscoring that the ability to “read” an acoustic scene is not intuitive but rather the result of years of practice and sensory adaptation.

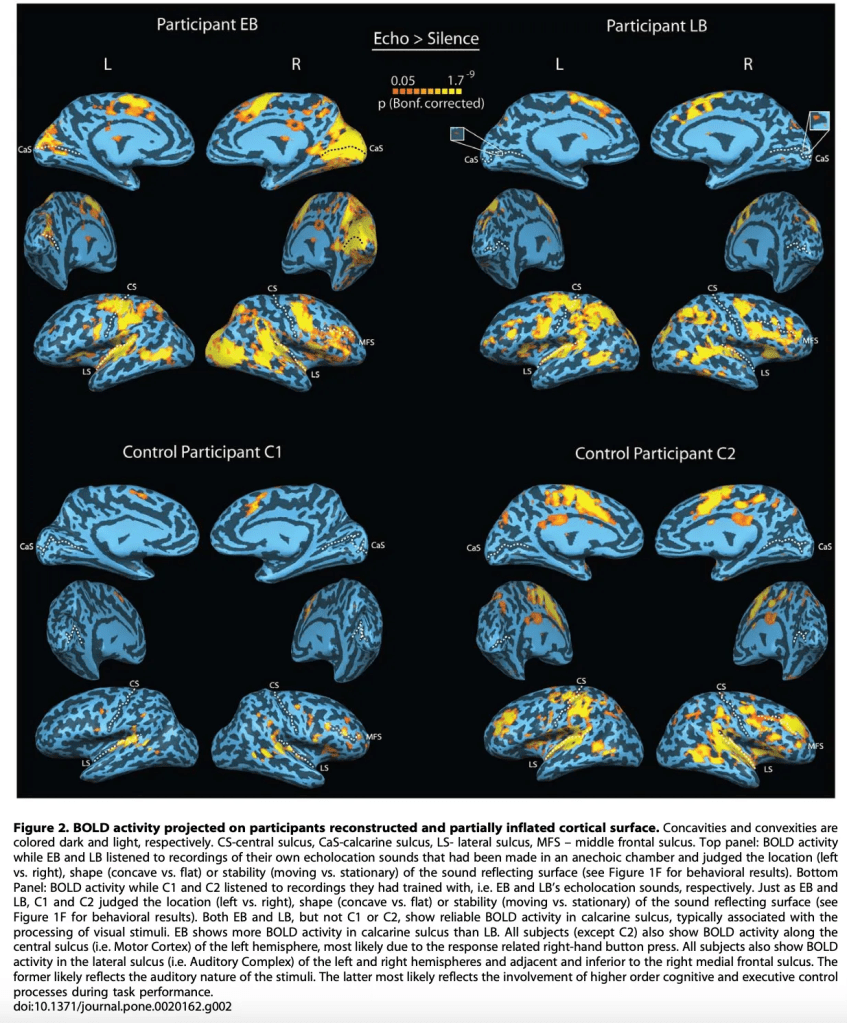

Moreover, the functional MRI results are striking, reinforcing the idea that the brain is a profoundly plastic organ capable of reorganizing itself when sensory experience demands it. In EB’s case, the images in Figure 2 show robust activation of the primary visual cortex—precisely around the calcarine fissure—as well as various associative areas that would normally participate in visual processing. In other words, in EB, the echoes generated by his own clicks are processed in regions that, in a sighted brain, are reserved for vision. LB, although he lost his sight much later, also exhibits a clear pattern of reorganization: his activation in visual cortex is less pronounced than EB’s, yet he still recruits pericalcarine regions along with extensive association cortices involved in high-level spatial and sensory analysis. Both subjects, as expected, also show activation in auditory cortex—the natural entry point for acoustic stimuli. In contrast, the two sighted controls reveal a completely different landscape: their brain activity is limited almost exclusively to auditory cortex, with very poor activation in visual association areas and none in primary visual cortex. This confirms that, without training or sensory necessity, the sighted brain does not “interpret” echoes as complex spatial information and therefore does not recruit visual circuits to process them. EB’s and LB’s brains, however, have transformed sound into an alternative form of spatial perception, reconfiguring circuits traditionally associated with vision to give meaning to a world perceived through echo.

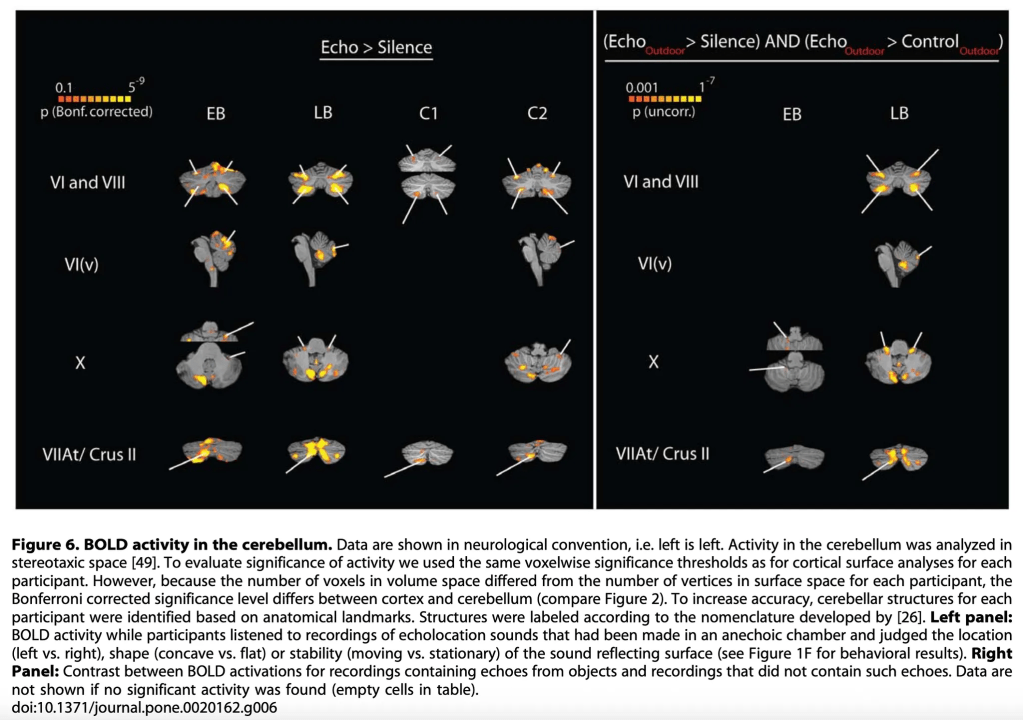

A particularly revealing finding emerged when the researchers examined cerebellar activity—a structure we often associate almost exclusively with motor coordination, but which in reality participates in a wide range of sensory and cognitive functions. In Figure 6, both EB and LB show marked cerebellar activation when listening to the echoes of their own clicks. This activation is distributed across regions such as lobules VI and VIII, the vermis, lobule X, and areas of Crus II—regions known to integrate fine sensory information and to participate in the temporal analysis of complex stimuli. In other words, the cerebellum of echolocators does more than modulate movement: it appears to be actively involved in decoding the acoustic landscape produced by their clicks, finely tuning the interpretation of the echoes and contributing to the spatial precision both demonstrated in the behavioral tasks. What is fascinating is that this cerebellar activation appears in both EB and LB, though with nuances: EB tends to show a more robust and widespread pattern, consistent with his very early blindness and long history of sensory adaptation. LB, for his part, also activates these regions, confirming that cerebellar reorganization does not depend exclusively on early-onset blindness, but also on the intensive and expert use of echolocation as a perceptual strategy. In contrast, controls C1 and C2 do show cerebellar activation, but it is far more limited and less specific. In them, the signal appears scattered and likely reflects basic auditory attention or general stimulus analysis, rather than fine echo processing or sophisticated spatial interpretation. In other words, their cerebellums hear, but they do not read the echo in the way echolocators do.

The final comparison is striking: in contrasts isolating the response to echoic sounds versus non-echoic sounds—and especially when comparing echolocators with controls—clear cerebellar activations emerge only in EB and LB. This suggests that the cerebellum, far from being a mere motor coordinator, becomes a sensory co-analyst, helping interpret the timing, direction, and variation of echoes, refining a perceptual capacity that replaces, at least in part, functions traditionally assumed by vision.

Thus, taken as a whole, the study shows that echolocation reorganizes not only the visual cortex but also the cerebellum, integrating it into a broader multisensory circuit that allows these individuals to “see” the world through sound.

I would like to conclude by saying that the documentary about Daniel Kish—the one that sent me jumping from echo to echo, dusting off old memories while also pushing me to read and investigate further—makes it clear that blindness is not an absence, but a fertile territory in which the human brain reinvents its own rules. Where the protagonists of Blindness saw chaos and dehumanization, and where the inhabitants of The Country of the Blind built an entire world without light, contemporary neuroscience shows us that the real brain—EB’s brain, LB’s brain, the brains of countless blind individuals—is capable of carving new pathways, reallocating functions, and transforming sound into an alternative form of vision.

Echolocation is not merely an extraordinary skill; it is living proof that perception is dynamic, malleable, and profoundly human. And perhaps that is why Kish’s story moves us so deeply: because it reminds us that seeing does not always depend on the eyes, but on the brain’s infinite ability to find meaning—even in darkness.

References

Scientific Articles

Thaler L, Arnott SR, Goodale MA. Neural correlates of natural human echolocation in early and late blind echolocation experts. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20162. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020162.

Thaler L, Goodale MA. Echolocation in humans: an overview. WIREs Cogn Sci. 2016;7(6):382–393.

Schmidt S, et al. Stimulus uncertainty affects perception in human echolocation: timing, level, and spectrum. Psychol Sci. 2013.

Blumenfeld H. Neuroanatomy Through Clinical Cases. 3rd ed. Sinauer/Oxford University Press; 2021. (For figures and anatomical descriptions).

Global Burden of Disease Vision Loss Expert Group. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years. The Lancet Global Health. 2021;9(2):e130–e143. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30425-3.

World Health Organization Website

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment

Videos

Leave a comment