By: Rodolfo Roman-Guzman (November 19, 2025)

This Saturday, I had the opportunity to visit the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto. There, I was pleasantly surprised to come across an extraordinary exhibition by the artist Jesse Mockrin. ECO, the title of her exhibition, invites us to explore the resonances of the feminine figure through 17 paintings and 8 works on paper, inspired by Baroque pieces from the AGO’s own collection (Jesse Mockrin on the Echo of Images).

Mockrin examines the violence and transgression inflicted upon the female figure within Greco-Roman culture. She reinterprets the essence of myths that have shaped our collective imagination, reframing them through a contemporary feminist lens.

For me, it was impossible not to find an immediate correlation with neuroscience.

The exhibition welcomes visitors with a summary of the legend of Echo. In particular, it refers to the classical myth narrated in Metamorphoses *(Narcissus and Echo),* where Ovid describes Echo, a nymph with a melodious voice who was used by Zeus (Jupiter) to distract Hera (Juno) with conversation while he courted other nymphs. One day, Hera discovers Echo’s true role behind their friendship and decides to punish her: she strips her of the ability to initiate speech, condemning her to repeat only the final words she hears. This symbolic mutilation of language transforms Echo into a tragic figure, a sonic presence that can exist only through the voices of others, deprived of her own discursive autonomy.

If we observe carefully, Echo is not merely a literary device: she is, in herself, a tacit description of echolalia.

The nymph loses verbal initiative, loses the ability to generate her own discourse, yet she preserves intact the ability to repeat. Her once melodious voice is reduced to an acoustic reflex, a literal echo of another’s words. This duality—loss of initiation with preservation of repetition—is precisely the clinical essence of echolalia, a phenomenon in which a person involuntarily and automatically repeats words or the final fragments of phrases spoken by someone else.

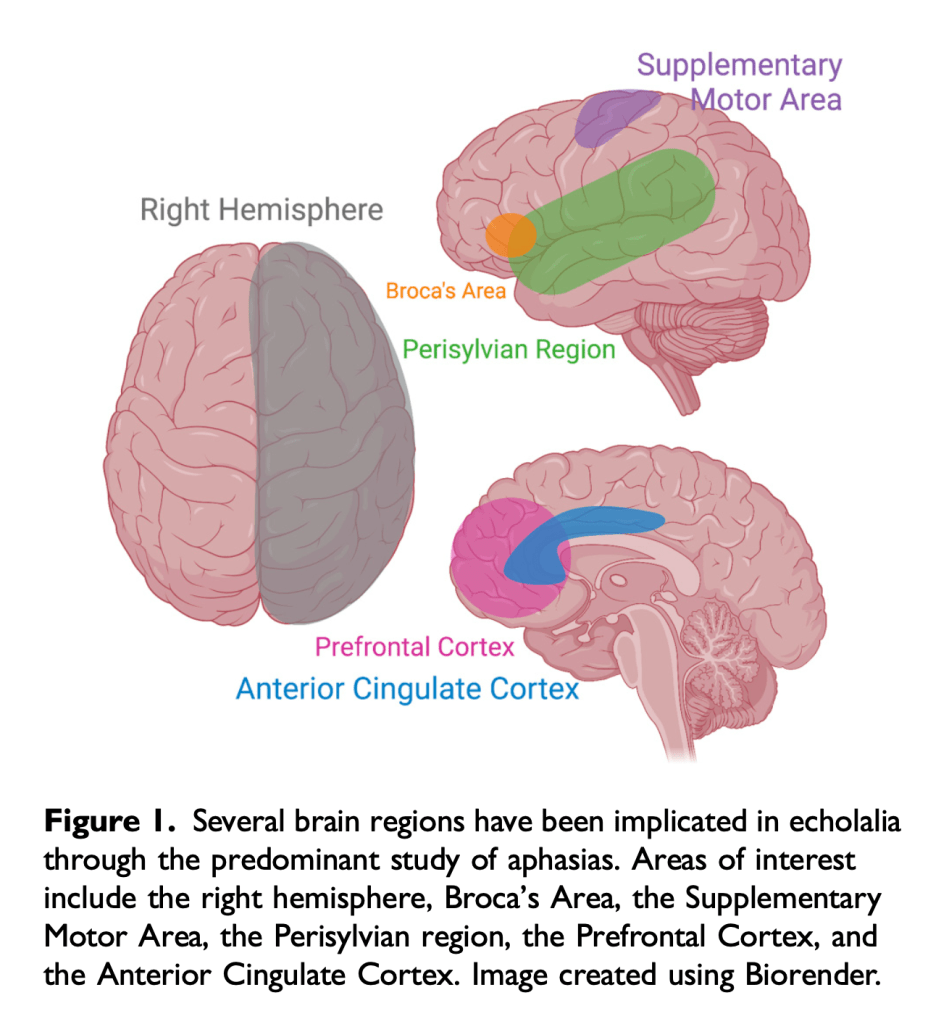

From a neuroscientific perspective, this parallelism with the myth becomes strikingly accurate. In disorders where echolalia emerges -whether in transcortical aphasias after stroke, in variants of primary progressive aphasia, or in neuropsychiatric conditions such as autism or catatonia— a crucial segment of the language network remains functional: the perisylvian circuit. This region includes the superior temporal auditory cortex, Wernicke’s area, the arcuate fasciculus, and premotor zones responsible for transforming sounds into articulatory gestures. When this circuit remains relatively preserved but the systems governing inhibition, executive control, or spontaneous language generation are disrupted, repetition appears “released,” unmoored from communicative intent.

In other words, echolalia emerges when the higher-order mechanisms responsible for modulating or inhibiting repetition fail, while the fundamental perception-imitation circuitry remains intact.

The article Echolalia from a Transdiagnostic Perspective explains this clearly: verbal repetition depends on an audiovisual imitation system located in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, the superior temporal gyrus, and the inferior parietal lobule, all under the supervision of an executive network responsible for inhibiting automatic responses. When this executive network is injured or becomes hypoperfused—for example, in the supplementary motor area (SMA), the anterior cingulate, or the middle cingulate—the ability to inhibit automatic activation of the perisylvian circuit is lost. As a result, repetition emerges unfiltered, like a neural echo (McFayden et al., 2022).

This model fits Hera’s curse in an almost poetic way. Echo retains the neurobiological machinery required for repetition: her perisylvian circuit, symbolically, remains alive. What she loses is authorship (and with it, autonomy)—the ability to initiate speech, a function more closely associated with medial and dorsolateral frontal regions responsible for linguistic planning and inhibitory control. Thus, the nymph is reduced to a stream of borrowed words resonating through her. Her once melodious voice—capable of winning Hera’s friendship—becomes nothing more than a resonance that mirrors the will of others.

And yet, the myth does not end there. Ovid takes Echo’s tragedy one step further when he makes her fall in love with Narcissus (Narcissus and Echo). Deprived of verbal initiative, Echo tries to confess her love by repeating the last words he utters, as if the passion consuming her were trying to force a linguistic autonomy she no longer possesses. Narcissus, unable to return her affection, rejects her with the same disdain he shows the rest of the world (he had already dismissed other nymphs before her). Fragmented by her own curse, Echo retreats into the mountains, where her body slowly wastes away until it disappears. Only her voice remains—*persistent, incorporeal, spectral—*trapped in the stones that repeat whatever they hear. Echo embodies a condition that Ovid, unknowingly, described with an accuracy we would now recognize as strikingly neuroscientific.

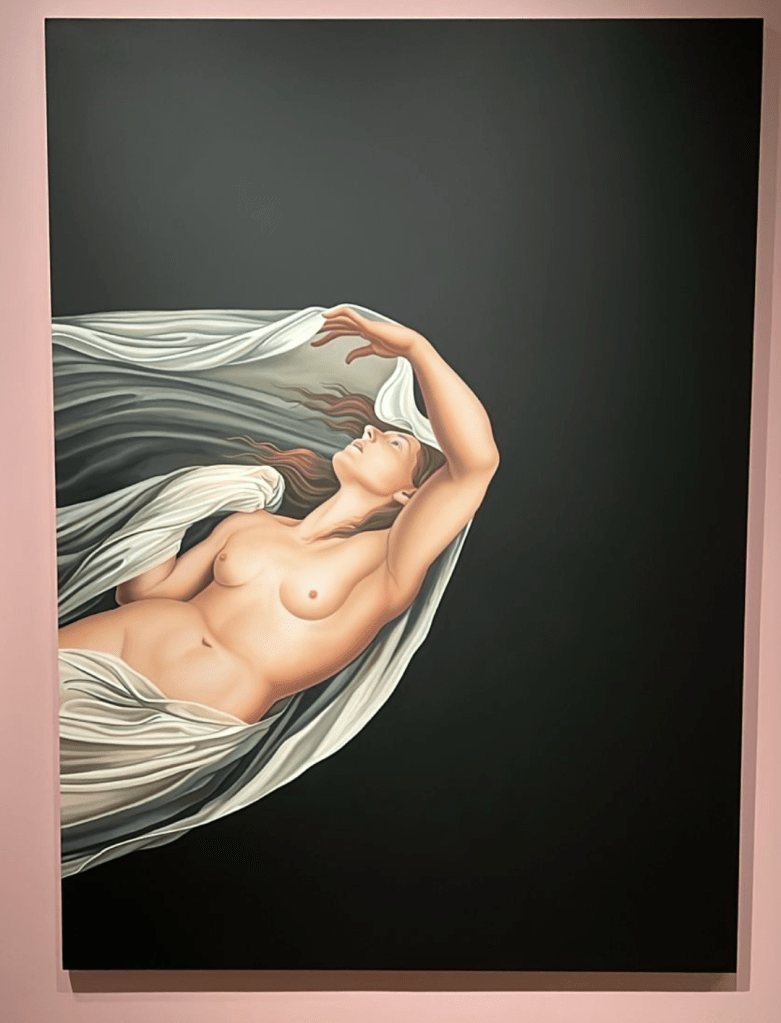

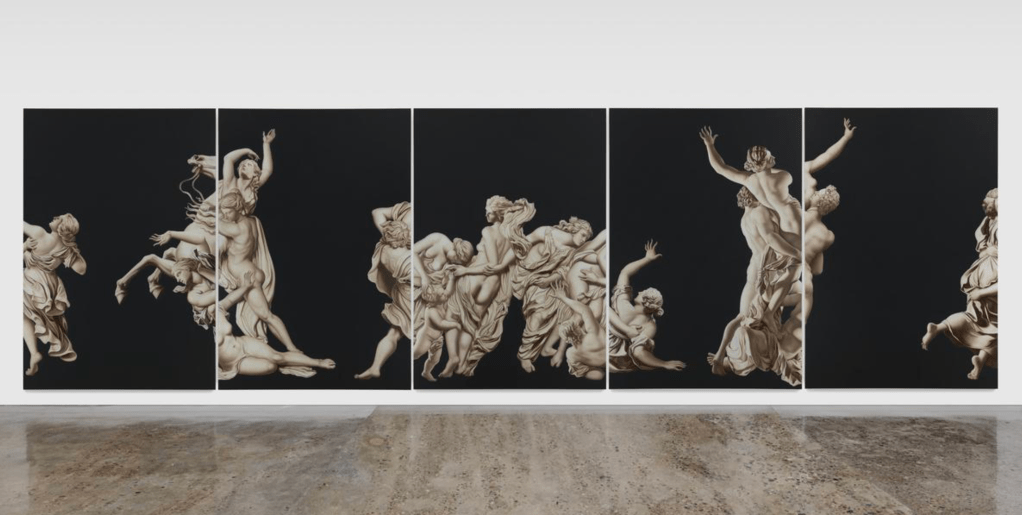

And as I was walking through the galleries of the AGO, I was struck by how Mockrin works, quite literally, with visual echoes: she fragments Baroque bodies, trims hands, torsos, and gazes, displaces them from their original context, and leaves them suspended against dark backgrounds—just as she does in The Descent (2024), a painting in which she uniquely reimagines the famous scene of the Abduction of the Sabine Women.

mage credit: Jesse Mockrin on the Echo of Images

This aesthetic of suspension in The Descent engages in a dialogue with the narrative of the Abduction of the Sabine Women, whose historical backdrop reveals the stark brutality of masculine power in the early days of Rome: a community composed almost entirely of men decides to abduct the women of a neighboring people to secure its biological survival and consolidate its political future. Classical iconography captures this moment of struggle and appropriation, where female bodies are torn from their space and their destiny. Mockrin reinterprets that same visceral energy without replicating the scene; instead, she follows its emotional resonance. Her falling figures do not depict the abduction itself, yet they evoke the loss of agency and the sudden collapse of feminine autonomy, transforming The Descent into a contemporary counter-echo of that ancestral gesture of domination.

Image credit: ¿QUÉ SIGNIFICA EL CUADRO DEL «RAPTO DE LAS SABINAS»?

This aesthetic decision to erase the setting and preserve only the gesture mirrors what the brain does in echolalia: it retains the mechanism of repetition, but loses much of the architecture that grants speech its initiative and context. Her paintings are, in a sense, the pictorial version of a liberated perisylvian circuit—images that resonate, already detached from their original narrative, much like a repeated phrase without an owner. And in this case, the beauty of Mockrin’s work lies in the fact that the echo is feminine, authentic, and free.

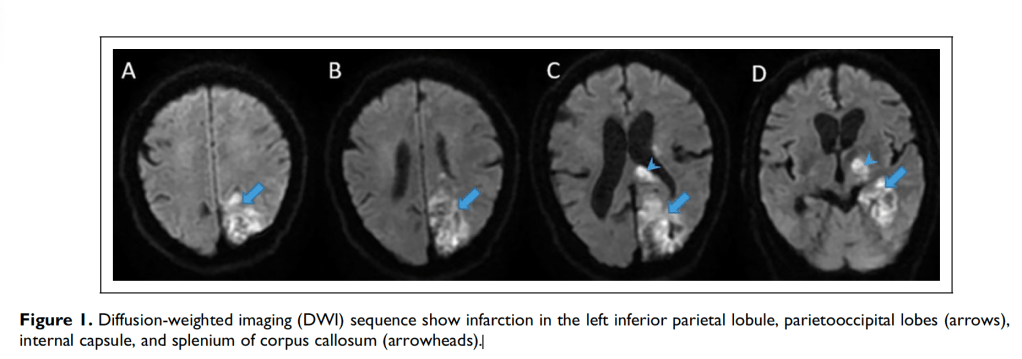

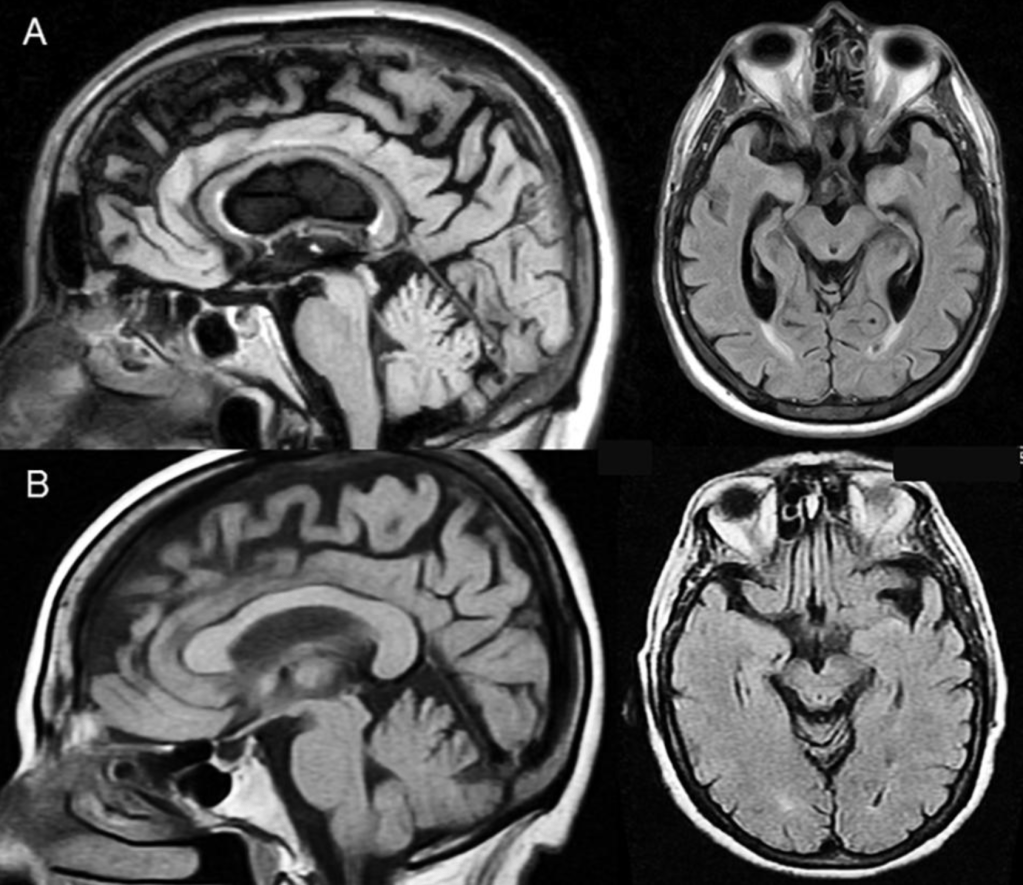

In aphasias associated with cerebrovascular disease, echolalia may arise not only as a consequence of a frontal “release” lesion affecting the perisylvian circuit, but also secondarily to deep posterior injuries that disrupt the broader language network. In the case described by Abusrair and AlSaeed, diffusion imaging shows an infarct involving the left inferior parietal lobule, parieto-occipital regions, internal capsule, and the splenium of the corpus callosum—that is, a neuroanatomically critical site where association and projection fibers converge, connecting temporoparietal areas with other regions of the hemisphere and with the contralateral side.

This pattern of injury does not completely destroy the perisylvian machinery for repetition, but it does alter the integration between auditory perception, semantic processing, motor control of speech, and interhemispheric networks. The resulting clinical picture is one in which repetition remains relatively preserved while spontaneous language and effective communication are impaired.

In this context, echolalia can be understood as an echo bouncing within a partially disconnected system: the words of others still find their way to articulation, even though the bidirectional exchange required for coherent discourse has been lost.

A similar phenomenon occurs in primary progressive aphasias (PPA). Ota and colleagues studied 45 patients with PPA and found echolalia predominantly in the nonfluent/agrammatic variant, with a distinctive pattern: poorer auditory comprehension, increased imitation behaviors, and a profile that, in some cases, resembled the classic transcortical aphasias, where repetition is preserved despite impairment in propositional language.

Torres-Prioris and Berthier, in their editorial “Echolalia: Paying attention to a forgotten clinical feature of primary progressive aphasia,” take this idea a step further: they propose that in the semantic variant of PPA and in the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia, degeneration of the temporal poles and anterior frontal cortex “releases” the activity of the perisylvian repetition circuit, turning the patient into a kind of verbal resonance chamber, where another person’s words rebound within a relatively preserved mirror system.

In neuropsychiatric disorders, a transdiagnostic reading points in the same direction. *McFayden and colleagues* propose that echolalia—whether in autism, schizophrenia, catatonia, or extrapyramidal syndromes—emerges when an audio-verbal imitation system (including the superior temporal cortex, inferior parietal region, and ventrolateral frontal areas) remains relatively preserved while the executive network that should modulate it becomes impaired: the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, supplementary motor area, and frontostriatal circuits.

Berthier and his group have described, for instance, patients with progressive supranuclear palsy and dynamic aphasia who present with irrepressible echolalia, in whom neuroimaging shows dysfunction within frontal and cingulate networks, leaving the verbal echo pathways effectively “unleashed.”

From this perspective, echolalia is not merely a “rare” symptom but the clinical trace of an imbalance: repetition networks that remain relatively intact, alongside deteriorated networks of linguistic control and initiative. This very asymmetry is what Mockrin makes visible on her canvases: she takes biblical and mythological narratives, strips away their backgrounds, and recomposes them into diptychs and triptychs where bodies appear to emerge from—or vanish into—the edges of the frame. What remains is the gesture, the frozen moment of violence or tension, repeated in minimal variations, as if the same scene were being reenacted again and again across the centuries.

And yet, in Mockrin’s work we are not confronted with an inert echo, devoid of agency or will, like Ovid’s Echo or the automatic repetition we observe in neurological practice. Here, the echo is not a residue: it is a deliberate intervention. Mockrin becomes the external agent capable of altering the natural organization of circuits—not biological ones, but cultural ones. In her act of deconstructing Baroque images, fracturing them, recomposing them, and forcing them to speak in a new register, the artist operates in a way that mirrors the pathology that releases verbal automatisms: she interrupts the usual flow of meaning and, in doing so, allows new resonances to emerge.

The visual echo she produces is not a passive reflection but a mechanism of revelation.

In this way, Mockrin becomes the artistic equivalent of a volitional “lesioning agent”: she intervenes in the iconographic fabric of the West and compels latent aspects of our cultural memory to surface. Because we—as a Western people, as Latinos shaped by the myths of Romulus and Remus, by the foundational violence of the abduction, and by the narratives that precede us—are also echoes and scattered fragments of a tradition that vibrates perpetually.

Our identity is a continuous reverberation of those same archetypal stories, resonating at shifting frequencies yet always emanating from the same vocal cords of Echo that shaped Greco-Roman imagination and, with it, the entire cultural lineage we inhabit.

References

Classical and Art Sources

Ovid. (2004). Metamorphoses (R. Tarrant, Ed.). Oxford University Press. (Original Latin text). Retrieved from https://www.theoi.com/Text/OvidMetamorphoses3.html

Foyer. (2024). Jesse Mockrin on the Echo of Images. https://readfoyer.com/article/jesse-mockrin-echo-images

James Cohan Gallery. (2024). Jesse Mockrin: The Descent. https://www.jamescohan.com/features-items/jesse-mockrin-the-descent

Historia del Arte 560. (2015). ¿Qué significa el cuadro del Rapto de las Sabinas?https://historiadelarte560.wordpress.com/2015/12/13/que-significa-el-cuadro-del-rapto-de-las-sabinas/

Scientific Articles on Echolalia

Abusrair, A. H., & AlSaeed, F. (2021). Echolalia following acute ischemic stroke. The Neurohospitalist, 11(1), 91–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941874420958847

Berthier, M. L., Torres-Prioris, M. J., López-Barroso, D., & Roé-Vellvé, N. (2021). Echolalic dynamic aphasia in progressive supranuclear palsy. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 13, 635896. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.635896

McFayden, T. C., Kennison, S. M., & Bowers, J. M. (2022). Echolalia from a transdiagnostic perspective. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 7, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969415221140464

Ota, S., Kanno, S., Morita, A., Narita, W., Kawakami, N., Kakinuma, K., … Suzuki, K. (2021). Echolalia in patients with primary progressive aphasia. European Journal of Neurology, 28(4), 1113–1122. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14673

Torres-Prioris, M. J., & Berthier, M. L. (2021). Echolalia: Paying attention to a forgotten clinical feature of primary progressive aphasia. European Journal of Neurology, 28(4), 1102–1103. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14712

Patra, K. P., & De Jesus, O. (2023). Echolalia. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565908/

Leave a comment